This blog accompanies my 2022 book “Understanding the New Global Economy. A European Perspective” with occasional short blog entries. The contributions are featuring new developments, actual debates, and new important analyses regarding developments in the emerging New Global Economy by connecting the reader to new and important online resources.

Will AI render all jobs obsolete?

3 November 2023

Today’s Financial Times reports that tech billionaire Elon Musk told UK prime minister Rishi Sunak there “will come a point where no job is needed”, adding that “AI will be able to do everything”.

Economists such as Richard Baldwin contest this view as “linear thinking (on jobs) in an exponential world” and point to the history of previous technological upheavals, namely the shift from farms to factories and the shift from factories to offices, where fears that there would be no more jobs were proved wrong.

Is this time different?

In Understanding the New Global Economy (p. 55-57), I have devoted a section to this issue. The major takeaways are:

- New technologies, such as robots and AI, can be labor-replacing or labor-enhancing. In the latter case they make workers more productive. Just think of AI-assisted surgery.

- Technological development in manufacturing often focuses on automating tasks and thus favors the replacement of humans by machines. Acemoglu and Restrepo (2018) argue that only if these technologies also boost productivity, as it was the case in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, this could boost production and labor demand. If the second effect offsets the first, net job losses can be avoided.

- Recent technological developments in robotics and AI are often designed to replace rather than enhance labor, hence, there is indeed now a real risk of rendering jobs obsolete.

- However – and this is crucial – net job losses can be avoided when we use proper incentives for directing technology to make workers more productive, and if workers are empowered to claim their fair share of the productivity.

In sum, AI must not make jobs obsolete. Rather, it is a question of societal choice:

- On the one side, there is the vision of a fully automated world. It is prominent with tech people. It features jobless economies and a universal basic income (UBI) as a substitute for labor income, probably even on a global scale as envisioned by OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman in his cryptocurrency project Worldcoin, where you receive cryptocurrencies conditional on a scan of your eyeballs, which is viewed as a first step towards a global UBI.

- On the other side, there is the idea of shared property based on inclusive development with better, more productive and well-paid jobs. This requires (re-)directing technologies with the right economic incentives, public investment in R&D, a supportive institutional framework and a participatory society in which productivity gains benefit people rather than enriching some elites, as Acemoglu and Johnson have recently argued.

It may well be that Elon Musk’s prediction will come true if society puts technological progress entirely in the hands of people like him.

But a different, more inclusive future is possible. We just have to take it into our own hands.

Geopolitical Tensions and the Future of Globalisation

19 June 2023

Geopolitical tensions are at a record high since Russia’s invasion in Ukraine, adding to the already existing tensions between the USA (and increasingly the EU) and China, while several important players in the Global South are not really willing to take sides. Increasingly, this conflict is viewed as one between democratic and autocratic political systems. Will geopolitics ultimately terminate globalisation?

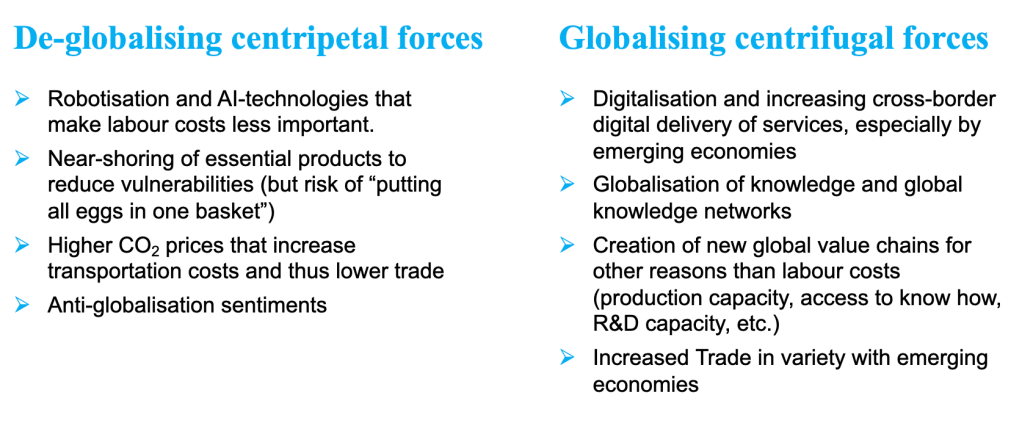

In “Understanding the New Global Economy“, I have suggested to view the future of globalisation as the outcome of competing globalising centrifugal and de-globalising centripetal forces:

My conclusion was that “globalisation is not over, but changing its character“. Under the impression of the recent development we have to add geopolitical tension on the centripetal, potentially de-globalising side. The outcome will crucially depend on the policy paths major players will pursue. However, they need to be aware of the economic and societal costs of their actions.

What will be the cost of a fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs? A recent IMF study reviews this issue.While the calculation by the authors amount to a substantial estimated loss of close to 2% of global GDP, they also review other studies, some of which calculate losses up to 12%. The authors conclude that, generally speaking, the cost are greater

- the deeper the global fragmentation (e.g., when trade takes place exclusively within blocs);

- if knowledge diffusion is reduced due to technological decoupling;

- if all trade and knowledge channels are fragmented simultaneously;

- in the short run (the calculation are made for the long run, including already some adjustments to mitigate the costs);

- for emerging markets and low-income countries that are most at risk from trade and technology fragmentation.

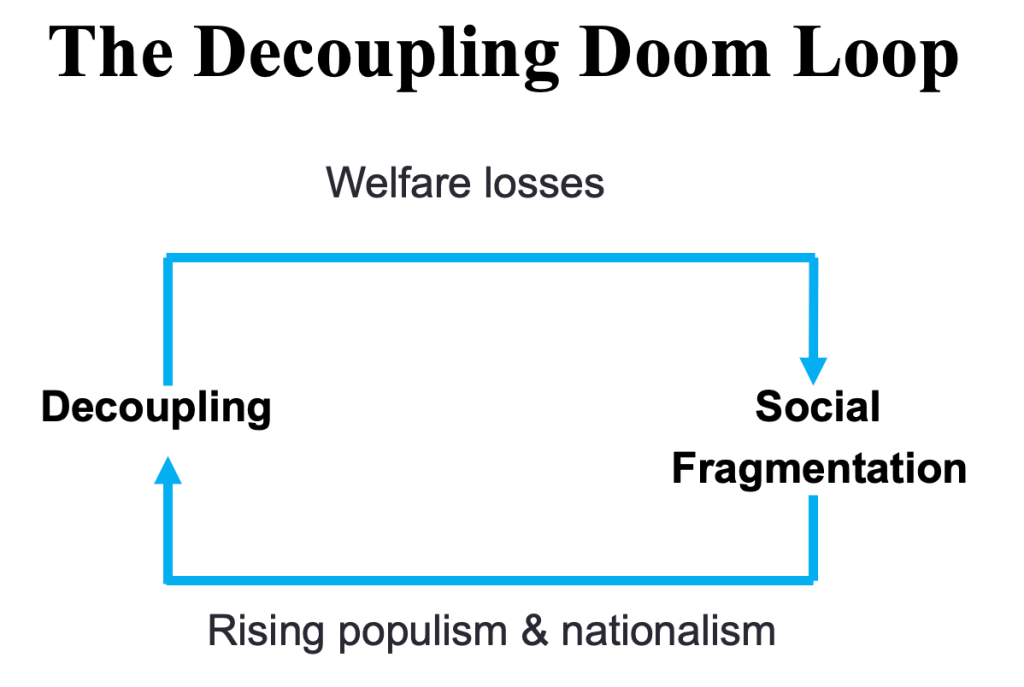

In sum, the cost of global fragmentation can become very high, and more often than not hitting the most vulnerable people and countries, thus also leading to social fragmentation. History has shown (recall the inter-war period) that this can easily lead to a doom loop of decoupling:

This risk has been recognised recently and let to a revival of industrial policy in advanced countries, with a view on protecting losers within a country from negative globalisation effects. Some observers have, however, raised concerns that the new focus could be simply be on “making decoupling work for the middle class”, possibly at the expense of other countries.

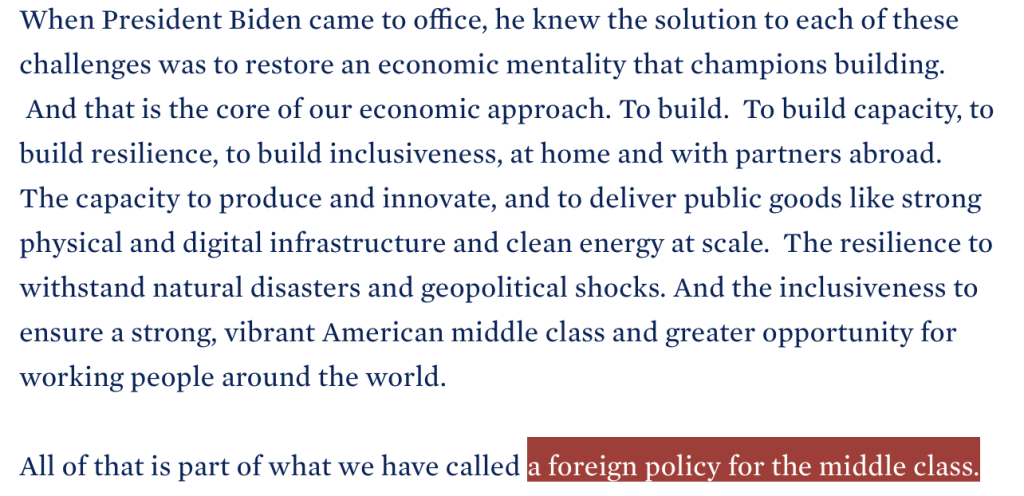

Interestingly, the language of Western policy makers has been changing recently. Ursula von der Leyen, President of the EU Commission speaks now of de-risking instead of decoupling, aiming at reducing vulnerabilities in supply chains, e.g. in energy, microchips, rare earth minerals, photovoltaic, batteries, etc. The US now adopts this language, too, as revealed by a recent speech by US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan,

In a nutshell, Sullivan calls for US foreign(!) policy for the US middle class. In his own words:

To do so, Sullivan lists five steps:

- A modern industrial strategy to promote sectors foundational to economic growth and strategic from a national security perspective (e.g. IRA, CHIPs and science act)

- “working with our partners to ensure they are building capacity, resilience, and inclusiveness, too.”

- “moving beyond traditional trade deals to innovative new international economic partnerships focused on the core challenges of our time.”…” (e.g., The Global Agreement on Steel and Aluminum”, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework,, U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, etc.)

- “mobilizing trillions in investments on emerging economies“(Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment – PGII).

- “protecting our foundational technologies with a small yard and high fence.” “These are tailored measures. They are not, as Beijing says, a “technology blockade.

Several US-commentators from various ideological backgrounds are remaining skeptical for different reasons. Europeans are still testing the new waters of American “friend-shoring” ideas. Big players in the Global South still have to be convinced that the promised trillions are sufficient to keep them in (or bring them back) into the Western camp, given their economic dependencies on China and Russia. And finally, it remains to be seen whether Sullivan’s “new Washington consensus” will be helpful to come back to better speaking terms with China.

While many issues remain open, we should not forget the potential power of a revival of a true multilateralism as a much needed countervailing force to promote international cooperation where it is most urgently needed: to address pressing global issues, like climate change and global health, to avoid devastating beggar-thy-neighbour policies, and in all cases where cooperation leads to superior outcomes for all. However, new multilateral efforts must be credible, especially to convince the Global South. This includes not only financial transfers, but a strong commitment to globally shared prosperity taking both the concerns and development aspirations of the Global South seriously.

Globalization is not passé. It is changing its character.

2 May 2022

Peter Coy, an econ columnist of the New York Times has talked to several leading economists on the state of globalization and concludes “Globalization isn’t over. It’s changing”. In a similar vein, and against the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Steven Altman and Caroline Bastion in their report on “The state of globalization in 2022” for the Harvard Business Review posit:

“Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to a new round of predictions that the end of globalization is nigh, much like we saw at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, global cross-border flows have rebounded strongly since the early part of the pandemic. In our view, the war will likely reduce many types of international business activity and cause some shifts in their geography, but it will not lead to a collapse of international flows.”

The changing character oof globalization, is the major thread running through my book “Understanding the New Global Economy. A European Perspective” (see the “Introduction”of my book, available as preview on the book’s website). To summarize my take on a premature diagnosed end of globalization, let me list a few points I have made in NGE:

- The process of globalization can be understood as increasing cross-border activities, such as trade, foreign direct investment, cross-border finance, labour migration, etc. Historically, sometimes but not always all these activities increase, but mostly not in uniform.

- Since the great financial crisis, especially merchandise trade has been stalling relative to global production (though rising in absolute terms, as observed by Coy). However, stalling trade globalization is not de-globalization. Global value chain (GVC) trade is still on a high level. To understand the stalling – and thus the end of increasing trade globalization – two points are important:

- Since approximately 2008, China is increasingly sourcing inputs to its manufacturing for the global economy domestically. This is mostly so because of China’s increased production capabilities in sophisticated (electronics and other) inputs rather than the result of a political strategy (such as “Made in China 2025”), at least before the trade war with the US started under the Trump administration.

- As Harvard’s Pol Antrás has argued global value chains may only go into the reverse when shocks to the economies are permanent rather than transitory. This does not mean that de-globalization is unlikely. Rather, we need to monitor the character of shocks, like Covid-19 and the war. The longer they prevail, the more likely GVCs will be reconfigured.

- In contrast to merchandise trade, trade in intangible goods, services, data and knowledge, is on the rise, thus changing the character of globalization.

- The emergence of digital money and finance will reshape the structure as well as the benefits and cost of global finance.

- The rise of emerging economies, especially China and India, will change the way globalization will be governed at the multilateral level.

To be sure, there is no guarantee that globalization will not go into the reverse. In fact, globalization can be viewed as the outcome of economic behavior by companies and households, reacting to both technological advances and policies. They may act as globalizing (centrifugal) forces or as de-globalizing (centripetal) forces. Rather than predicting the end of globalization by extrapolating some actual trends into the future (just have a look at this Figure by Jeffery Kleintop), careful analyses of all these forces are needed.

With respect to the war, of course, political developments are key. The more determined policy makers are, and the more they convince corporations that a changed policy stance towards Russia, and probably even more importantly towards China, will be permanent, the more likely business will reshape the geography of their GVCs. In this respect the potential impact of some key points (stressed in bold letters by me) made in a recent speech of US Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, can hardly be overestimated:

“…we need to modernize the multilateral approach we have used to build trade integration. Our objective should be to achieve free but secure trade. We cannot allow countries to use their market position in key raw materials, technologies, or products to have the power to disrupt our economy or exercise unwanted geopolitical leverage.

…

Favoring the friend-shoring of supply chains to a large number of trusted countries, so we can continue to securely extend market access, will lower the risks to our economy as well as to our trusted trade partners. We should also consider building a network of plurilateral trade arrangements to incorporate elements of the modern economy that are growing in economic importance, especially digital services. We should harmonize our approaches to protecting the privacy of data. And a modernized trade system will also require the ability to effectively enforce trade policies and practices, both multilateral and bilateral.”

The key point is that the role of policy in reshaping globalization will increase. This can have lasting effects on the character and geography of globalization. Rather than postulating the end of globalization we need to have a close look at this emerging new global economy, and what it holds in store for the wealth of nations and people.

Postscript

See also the insightful piece written by World Bank’s Michele Ruta for Vox EU from 5 May on “How the war in Ukraine may reshape globalisation“. From the abstract:

The war in Ukraine has suddenly increased geopolitical risks. This column argues that firms will respond to the shock by reassessing security-related risks, leading to changes in the structure of supply chains. But given the capital in place, the cost of searching for alternatives, and factors such as wage differentials across countries, this process is likely to be gradual rather than sudden and will affect different sectors and products differently. It will not result in a reversal of globalisation, unless it is supported by pronounced government intervention.